Retracing The Tracks Of The Historic Big Bear Run

Racing thru time, rediscovering the forgotten routes of the legendary 1960 enduro.

So many things begin in bars, and many of them are good. More than one adventure story has arisen from a saloon wager. A 2-cent bet in an Alaskan bar which got upped to $1,500 led Thomas Lloyd to become the first person to summit Denali, the highest mountain in North America. Dr. Horatio Nelson Jackson made a $50 bet in a San Francisco club which led him to become the first person to cross the United States in an automobile. And, as rumor has it, a couple of guys in a Los Angeles bar made a bet on New Year’s night in 1921 over who could make the 100-mile ride to the mountain town of Big Bear Lake first.

This bet did not specify a route, so one rider chose the direct way via paved roads, and the other elected for the back way up the mountain through the desert on dirt. The entire idea was the sort of madness that seems appropriate for a bar bet because it was early January at the time, and the paved route ended up being blocked by snow. However, the one rider that took the back route managed to make it to Big Bear to win the bet. The story spread among local riders and soon others wanted to test their mettle taking on the challenge, which eventually snowballed (no pun intended) into a full-fledged annual race.

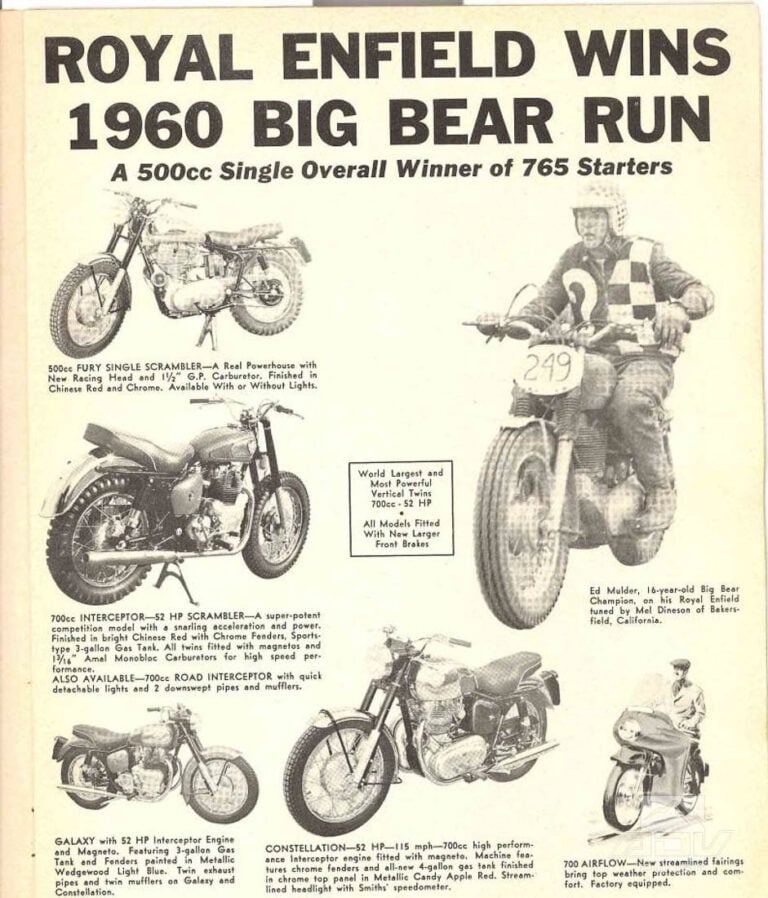

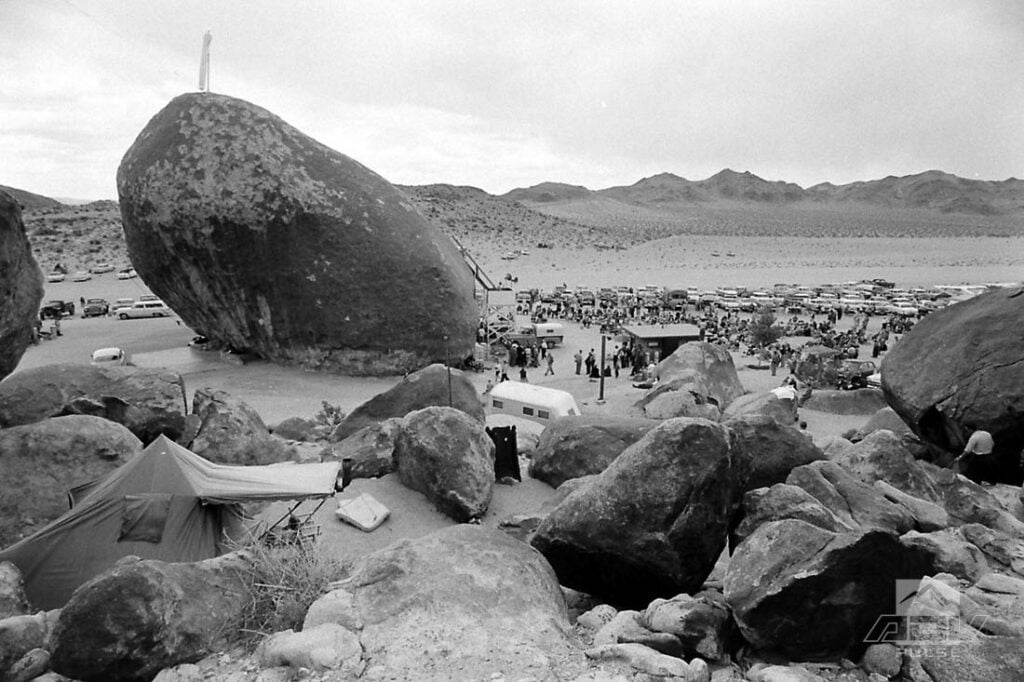

After the first running of the then-unnamed Big Bear Motorcycle Run in 1921, the race always went up the mountain from the desert. While it’s said the race reached its height in the 1950’s, in 1960, nearly 1,000 riders lined up for the historic event. By then it had become one of the world’s largest motorized sporting events, attracting legendary competitors like Bud Ekins, Aub LeBard, and Vern Robison.The last complete running of the Big Bear Run in 1960 holds a story that’s tough to repeat today: A young kid, beating many seasoned professional riders in a high-profile race. At age 16, Eddie Mulder lined up aboard a Royal Enfield Fury 500 along with 765 other motorcycles, ready to take on the three-loop, 150-mile course through some of Southern California’s most challenging riding terrain. In an unconsciously perfect way, the completely unknown Mulder would do the entire race with a huge question mark worn over his riding leathers — the sign of a probationary member of the Checkers Motorcycle Club.

The kid from Lancaster, CA, was clearly fired up to race. Despite being the last rider to leave the starting line, Eddie pushed to get into the top 20 by the end of the first loop. During the second loop, that same aggressive riding drove him straight into a boulder which snapped his right footpeg off. Mulder kept going, and for a full 50 miles — 1/3 of the race — he rode some of the toughest sections with his right foot wedged atop the engine case.

After replacing the footpeg at a checkpoint before the final loop, the challenges didn’t end. Misjudging a switchback sent Mulder off the track and into a ravine, resulting in an impact which tore the header pipe away from the cylinder. Clawing his way back onto the course, the 16-year-old got things sorted out as best as possible under the circumstances, but other mechanical drama remained. In his own words from a 2024 interview “I heaved the bars into shape and kicked the header pipe back into place. Couldn’t do anything about the broken shock absorber, so I rode the rest of the race on just one.”

Four hours and 21 minutes after leaving the start line, Mulder crossed the finish. Exactly 193 riders would finish that day, and 192 of them were still behind him. Mulder’s win would catapult him from obscurity to national fame, landing him magazine covers and sponsorships almost overnight. What no one knew at the time was this would be the last ‘complete’ running of the Big Bear Run. The sheer amount of wheeled traffic associated with an event like this is claimed to have led the California Highway Patrol to shut the race down the following year, although some organizational chaos during the 1961 attempt is also thought to have played a part in its final demise.

A Bike Inspired By “Fast” Eddie’s Historic Win is Born

To honor that historic win, Royal Enfield recently introduced the Bear 650, a tribute to “Fast” Eddie Mulder. Powered by a 650cc inline twin, delivering 47 horsepower and 41.6 ft-lbs of torque, the Bear 650 boasts ABS disc brakes, fuel injection, a six-speed transmission, 43mm upside-down forks, and a TFT display. Even though the modern bike is mechanically quite different from Mulder’s Fury 500 in many ways, it’s similar in more ways than just the look.

Royal Enfield’s Fury 500 was a tuned race version of the Bullet 500, intended to compete against the flat-track BSA Gold Stars and Triumph T100s that were dominant at the time. The Fury used a “Big Head” version of Royal Enfield’s 500cc single engine, which was first introduced in 1959. The “Big Head” name arises from the larger cooling fins on the head, but this engine also integrated rocker boxes with the head casting, used higher lift cam profiles, had a larger inlet valve, a 7.3:1 compression ratio piston, and a 13/16” Amal Monobloc carburetor which boosted power to a respectable 40hp for the era. The Big Head engine was also designed to allow owners to further tune it to their liking. Californian Royal Enfield dealer and tuner-sponsor Mel Dineson prepared the 500cc bike for the race, and according to Mulder, it “would pull the cork off any 650.”

For better or worse, in some ways the 2025 Bear 650 can provide a fairly “authentic” classic riding experience. Both bikes share a 19” front wheel, but the 2025 model sports a 17” rear compared to an 18” on the older version. The bikes share the same 5.1” of front suspension travel, although clearly the 43mm inverted Showa Big Piston forks on the Bear 650 offer an edge to some degree over 1960’s technology. With 4.5” of travel in the shocks, the 2025 Bear 650 provides over 1” more rear suspension travel than Mulder’s bike did. However, between the twin-cylinder engine, chassis, and electronics, the overall package of the modern bike is some 50-60 pounds heavier than the original version.

With similar power-to-weight ratios and suspension travel, it could arguably be the brakes that most separate the performance of these two bikes spanning 65 years. Entering a corner too hot on a mountain race course with vintage drum brakes is a completely different experience compared to navigating the same scenario with floating calipers grabbing a 320mm rotor up front and 270mm rotor on the rear.

Retracing The Original Route

Recently, Royal Enfield held a tribute ride that was a homecoming for the Bear 650 in the place that inspired its name. After attending the event and delving into some of the history of the Big Bear Run, we came across some old maps of the course from the early years. This spawned the idea of taking the Bear 650 for a more intense off-road excursion — one that would retrace the tracks of the Big Bear Run racecourse.

The trails for the race changed from year to year. Typically there would be one or two loops out in the desert before traveling up the mountain to finish in the town of Fawnskin on Big Bear lake for the final leg. Some articles from the time indicate Mulder’s historic 1960 race win involved two 45-mile loops between the desert and foothills, then a final 68-mile loop up to Big Bear and back down the hill to finish in Lucerne Valley. The exact route was kept a secret until the day of the race, marked out by sacks of lime a few hours before the start.

Due to the expansion of the 29 Palms Marine Base, portions of the Big Bear Run’s original desert loop through Johnson Valley are now off-limits, except for during special race events. However, the vast majority of the original race course is still available for anyone to try today — if you can find it.

Using a combination of old maps and archived stories published from the races, we were able to recreate two common routes from various years going up the mountain — both starting in the Soggy Dry Lake area and ending in Fawnskin. One went farther east through Means Dry Lake then to Giant Rock and Pioneertown, before heading up the hill to Big Bear. The other took a more direct and technical route through Rattlesnake Canyon wash up to Lake Baldwin.

We opted to split up the two routes into two days to allow more time to enjoy the scenery and explore interesting sites along the way, making it more of an adventure than a go-for-broke race. Given many unknowns, we also opted to run the toughest sections of the course essentially backwards — climbing the comparatively tame parts and descending the more technical ones. Although, referring to trails as either tame or technical can be relative. Fast-forwarding to a preview of our ride, while descending one of the “tame” sections we had just climbed the day prior, we paused at the top of a steeper portion just in time to see a couple two stroke enduros simultaneously looping out mid-trail as they attempted the climb.

Day 1: Descent To The Desert

Setting out to retrace the path of this historic race from our base of operations on the eastern edge of Big Bear City, meant we first needed to get to the starting line near Soggy Dry Lake roughly 4,000 feet below. Descending from Big Bear Valley towards Lucerne Valley along Highway 18 provides miles of fun curves with distracting views of the vast desert landscape below. This stretch of twisty pavement also provided a good warmup to become more familiar with the Bear 650’s handling characteristics.

After reaching the valley floor, a short stretch of pavement headed east along Highway 247 leads to the turn off for Bessemer Mine Road. Almost as wide as the pavement of Highway 247 in places, Bessemer Mine Road is a flat, fast, largely straight dusty dirt road leading towards the Big Bear Run’s traditional starting location. The near-straight line of dirt begs to be ridden fast, but this first unpaved section is where the limited travel of the Bear 650 started to reveal itself.

The bike’s power delivery and ergonomics beg to be ridden at modern-day adventure bike speeds off-road, until a rock or G-out of just the right size reminds you of its heritage. Speed runs and sliding the Bear 650 around on the dry lakebed provided confidence in the overall handling of the bike off-road. Playing around in the vicinity of the original race’s start also made me wonder if the present-day ruts, cutting hidden wheel-grabbling lines across the otherwise flat lakebed surface, were mirrored by similar potentially disastrous features for a bomb-run race start in 1960.

Surprisingly, once you get off the hard pack and into the sand, the heavy engine and low chassis perform far better than might be expected in the deeply sandy roads which are the dominant feature of this portion of California desert. Leaving the roads altogether and throwing the Bear 650 into the dunes would prove to be one of the most fun and relaxing parts of the entire two days of riding. It’s a far cry from pitching around a 450 weighing nearly half as much, but the Royal Enfield felt completely at home in the bottomless sand.

Tire choice almost certainly played a part in the Bear 650’s capabilities in these conditions. While the stock MRF Nylorex offer good enough grip for typical fire roads, they aren’t the best choice for challenging terrain. A last-minute call to Three Brothers Racing in Costa Mesa, CA resulted in the Bear 650 sporting new Dunlop Trailmax Raid 40% street / 60% dirt dual sport tires for the project. I’d recently used these tires on a trip to the Grand Canyon where they proved themselves on rocks, loose gravel and soft sand. Given how well they worked in those off-road situations, I was confident the Trailmax Raids would be an asset getting us through the even deeper sand and chunkier rock sections we’d encounter on this trip.

Weirdness In The Desert

In the first few miles, the Big Bear Run course passed by stunning natural desert features, quirky remote infrastructure, and in at least one case, a combination of those two things.

Once widely accepted as the largest free-standing boulder in the world, Giant Rock derives its name by being a giant rock. This big stone has played host to Native Americans who revered it as a sacred place, a 1968 UFO convention, and a German prospector, Frank Critzer, who dug his home underneath it.

As the sun began to rise on March 24, 2000, the nearby town of Landers woke to a loud rumbling sound. It was later discovered that Giant Rock was now somewhat less giant, as a huge section had broken off. Speculation still swirls about how and why this massive landmark fractured in the way it did. Had the dynamite explosion many decades earlier which killed Frank Critzer in his subterranean home somehow weakened the stone? Had aliens arrived earlier that evening, and upset by the lack of a space convention zapped the rock in two and left? Reasons are unclear, but it’s an impressive site to see.

Even if some teenage aliens had indeed vandalized this ancient landmark in protest for missing out on an intergalactic tailgate party, most of the extraterrestrial visitors to this area are apparently magnanimous. It’s said that visitors from the planet Venus provided instructions to George Van Tassel for the construction of the Integratron in nearby Landers. Tassel was a friend of Giant Rock’s former resident Frank Critzer, and from 1957 to 1959, Tassel erected the domed structure with funds provided by donors, including Howard Hughes.

Research for this story did not turn up any reports of Big Bear Run competitors stopping in to the Integratron for a mid-race Sound Bath, but the site provides present-day riders with an air-conditioned gift shop, complete with cold drinks and well water available.

Scratching towards the edge of the desert and nearing the mountains, Pioneertown was another typical spot on the map riders would pass by before ascending towards Big Bear Lake. Originally built in 1946, this purpose-built town was designed and constructed in an 1880’s-style as a movie set for Western films. We made a quick pit stop of our own at Pappy & Harriet’s to grab lunch and a cold drink.

While climbing Burns Canyon towards the higher elevations, we passed the intersection leading towards Rattlesnake Canyon. Typically the Big Bear Run races would climb this technical section up towards Big Bear, however several reports indicate the 1960 race descended this part. Tomorrow, we would seek out the tracks of Eddie Mulder, and see how the Bear 650 performed in the rocks and sand of this infamous route.

Our final 25-mile stretch towards Big Bear was likely much more fun than what Mulder and the 1960 Big Bear Run competitors would have encountered along this same section. We were riding in late June. Presuming we had the course exactly identified based on the collection of old accounts that research had dug up, those original racers would have been competing along these routes in January. As an example of how brutal mid-winter conditions here can be, legendary racer and stuntman Bud Ekins was reportedly unable to finish the 1955 Big Bear Run due to his carburetor icing up.

After cresting Nelson Ridge, racers looking down on Baldwin Lake in 1960 would have likely seen a winter wonderland landscape. In spite of the seemingly impossible riding conditions, I’m sure that view must have fueled some hope in knowing Fawnskin was a relatively short distance away, and they would soon again begin descending into the drier and warmer desert landscapes below.

For our part, we had the luxury of stopping for a photo or two, exploring an abandoned mine shaft, and contemplating the thought of hundreds of limited-travel motorcycles charging this same terrain much harder than we were. We rode towards a finish line of trying to gain insight into a historic race, while racers of the time risked everything for a trophy.

Scenery changes drastically and repeatedly throughout the 4,101 feet of climbing along Burns Canyon between Pioneertown and Big Bear. Desert scrub brush and creosote fade almost imperceptibly and are replaced by groves of Joshua trees. Oppressive heat of mid-summer desert riding is greeted by a refreshing drop in temperature as pine trees begin to appear towards the upper elevations.

Even without everything being covered in snow, some optional sections of this route proved to be more than a little challenging. These optional sections also proved to be the most fun in the majority of cases. However, fun is relative, and riding the mountains of Southern California in June versus January are two very different things.

Day 2: Deep History And Deep Sand

Anticipation of what was expected to be a second day filled with potentially gnarly riding was preceded by a fun and scenic ride through the history. With our plan to run the course backwards, we started on the north shore of Big Bear Lake in the town of Fawnskin — the traditional finish line for the Big Bear Run.

In 1915, the town of Pine Knot (today known as Big Bear Village) on the south side of the lake was just getting started. Traveling there from San Bernardino required taking the Rim Of The World Highway from Running Springs through Green Valley Lake to Holcomb Valley, eventually reaching the north shore of the lake, then continuing another two hours around the lake to the fledgling village on the south shore.

Developers William Cline and Clinton Miller saw an opportunity to build up the north shore of the lake at the point where the unpaved Rim Of The World Highway entered Big Bear Valley. Purchasing 700 acres of land in the Grout Bay area, Cline and Miller started subdividing and building. In 1917, the new community was dubbed Fawnskin and by 1924 the San Bernardino Sun newspaper announced the beginning of construction for a 218-room hotel.

As it would turn out, the Sun’s article was published prematurely. 1924 was also the same year that the Arctic Circle Highway (today known as Highway 18) was completed to the Big Bear Dam, replacing a section of the Rim Of The World Highway. A new bridge across the dam redirected traffic directly to Big Bear Village and the developers of the new hotel in Fawnskin saw the writing on the wall.

Fawnskin had essentially been bypassed. While the community still exists today, the stagnated growth is perhaps best represented by the Fawn Lodge. Positioned like a centerpiece at the heart of the town, this lodge was one of Fawnskin’s earliest buildings, built in 1917. Although it still stands today, the lodge has been closed since the late 1970’s.

Just north of Big Bear Lake, high up in the mountains, the Big Bear Run’s route passes through a sleepy valley that was once a commercial center for the region. The remote and picturesque Holcomb Valley is the former site of Belleville, which was once in the running to become the county seat for San Bernardino. Named after Belle, the first child born in the town, Belleville is yet another boom-and-bust story of gold mining settlements in the fledgling West. A single restored cabin is the only significant structure remaining from the town which had grown to nearly 1,500 people at its peak.

Only slightly off the beaten path through Holcomb Valley and the former site of Belleville, two gravesites have become official stops along the Gold Fever Trail. Entering the valley from Fawnskin, the first grave reached is that of Charles Wilbur. Wilbur was the first tax assessor in San Bernardino County, and had specifically requested to be buried next to his favorite pond near the former site of Belleville. The second gravesite is for “Ross,” and is a bit more mysterious. While not much is known about who Ross was or why his grave somehow garnered distinction over the years, we tossed a pinecone onto the site, as the tradition here holds.

Retracing this portion of the Big Bear Run’s route offers the distinct feeling of connecting three very different chapters in California’s history. A mere 51 years after Holcomb Valley’s gold rush ended in 1870, a fateful Los Angeles bar bet in 1921 would mark the beginning of the Big Bear Run, and 65 years after Eddie Mulder’s historic win of that race in 1960, we were out here searching for his tire tracks in 2025.

High Valley To Low Desert

Before even reaching the deep sand washes of Rattlesnake Canyon, unexpectedly rocky climbs along Smarts Ranch Road had to be navigated. While the power delivery of the Bear 650 was more than ample for all the situations we encountered, maximum suspension travel being limited to barely over 5” meant occasionally dabbing through portions of the course and carefully choosing lines through the rock gardens was all but necessary to preserve the bike. In spite of its limited suspension travel, the Bear 650 boasts a respectable 7.2” of ground clearance — only 0.08” less than a 2024 BMW R 1300 GS.

Riding this portion of the 1960 Big Bear Run’s course offers an interesting perspective on what the competitors might have experienced. During our descent through Rattlesnake Canyon, as the sand washes widened, and the canyon walls gradually became lower, views of Lucerne Valley in the distance started to be revealed. Mentally, it felt like a more challenging portion of the route was about to end, and replaced with faster, flatter, and firmer racecourse. That feeling never had the opportunity to take hold, as it seems the competitors might have found the sands of Rattlesnake Canyon easier to ride than the chopped up chaos on the valley floor.

Given the vague and ever-changing landscapes of Johnson and Lucerne valleys, it’s entirely likely we deviated from the 1960 course by a little, or perhaps a lot, or perhaps we followed it perfectly. It’s difficult to say, however if we were on the correct route, the competitors would have exited Rattlesnake canyon by navigating a steep ledge out of a tight sand wash, only to be thrown into numerous switchbacks clearing mini canyons shaped like failed urban storm drains.

Every few meters, another steep and loose descent threatened to deposit you over the side and into a bike-extraction project. 90-degree or even hairpin turns to stay on course were as clearly visible as street signs in suburban Managua. Whether we were on the exact course or not, this whole valley is a topographical mess for miles in every direction. In other words, it’s perfect for racing. With nearly 800 motorcycles aiming for the same canyon, it’s easy to believe we were following a patchwork of various rider’s good choices and bad decisions.

The Final Stretch

After passing what I’m sure was one of the background actors from Beyond Thunderdome rallying an apocalyptic buggy of some sort at obscene speeds (sans helmet, glasses, or shirt) and nearly taking us out on a blind curve, we reached the end of the trail at Highway 247 and headed into Lucerne Valley. The live band playing at Cafe 247 as we rolled up for a much-deserved meal made us feel like we had indeed just completed an event of some sort. What that event was, we weren’t exactly sure.

We know we had found and ridden the two traditional routes going up the mountain of the original Big Bear Run, but no doubt there are more tracks out there lost to time. Royal Enfield’s Bear 650 seems to check most of the desired boxes a modern motorcycle could in order to honor Eddie Mulder’s heroic effort, but just how close does it come to allowing someone to experience what those early races might have been like behind the bars?

I suppose it’s all moot. The original race was a bar bet that became an event. This project was a crazy idea that became a magazine feature. Our conclusion in Cafe 247 might have been very similar to that of those first two Big Bear Run riders in 1921, finally stopping to talk about the ridiculous journey they’d just completed, likely over a drink and a meal someplace.

Possibly the most unfortunate aspect of this project is that no wagers were made at its conclusion. After all, why couldn’t the tracks we’d laid out become the start of a popular new Scrambler route for riders to test their resolve? We’d just completed a fairly harebrained ride, having incorporated a motorcycle specifically intended to pay homage to an unexpected race victory decades earlier, and were in a cafe. Not a bar, but it’s close enough.

For my part, I’ll include running #249 on my number plate as part of my wager.

Maps and GPS Tracks

Want to do this ride? A large interactive map and downloadable GPX Tracks are available free.* Note: Zip downloads don’t work with the Facebook app. Download using a regular browser such as Chrome, Safari etc.

* Terms of Use: Should you decide to explore a route that is published on ADV Pulse, you assume the risk of any resulting injury, loss or damage suffered as a result. The route descriptions, maps and GPS tracks provided are simply a planning resource to be used as a point of inspiration in conjunction with your own due diligence. It is your responsibility to evaluate the route accuracy as well as the current condition of trails and roads, your vehicle readiness, personal fitness and local weather when independently determining whether to use or adapt any of the information provided here.

Photos by Kevin Wing

Notify me of new posts via email

Loved this story about a very special place I have been lucky enough to visit in the past, modern Big Bear with its many cabins and vacation homes.

Loved it, Jon

Opps. Just returned from Botswana, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Zambia where you’ve roamed!